Summary

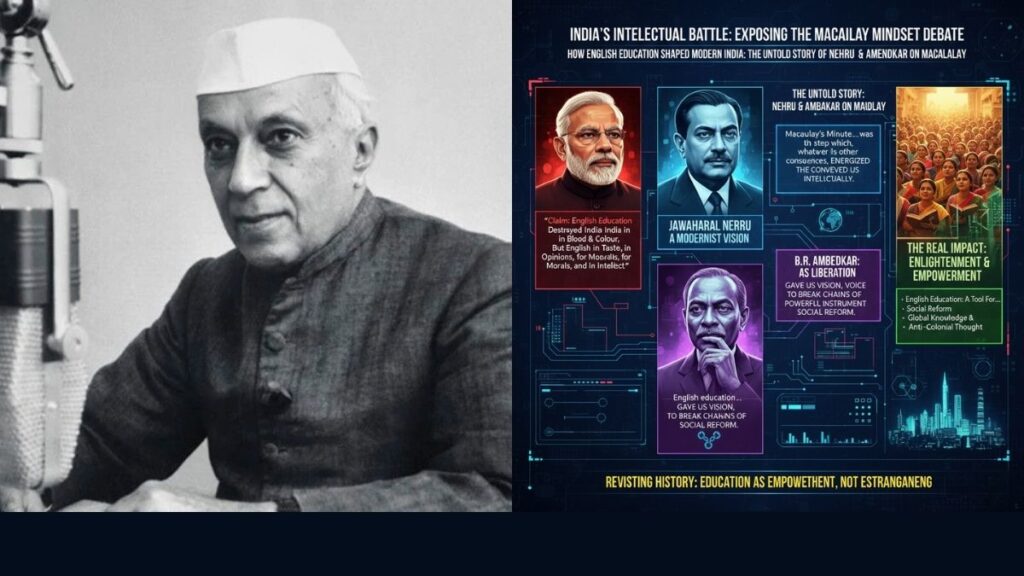

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent remarks on the so-called “Macaulay mindset”—delivered during the Ramnath Goenka lecture on November 18—have stirred debate across the country. Modi argued that Thomas Babington Macaulay’s introduction of English education severed India from its cultural roots, produced Indians who “looked Indian but thought like the British,” and pushed the nation toward an unquestioning dependence on Western models and ideas.

However, when we revisit the writings of Jawaharlal Nehru and B.R. Ambedkar, a very different picture of Macaulay emerges—one that sharply contradicts Modi’s selectively framed narrative. Their perspectives expose how oversimplified and historically inaccurate Modi’s understanding of English education and Macaulay truly is.

Nehru: British Authorities Initially Opposed English Education in India

In The Discovery of India, Nehru makes it clear that the British Empire was not eager to teach English to Indians in the 18th century. According to him:

- Reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy learned English privately, long before English schools existed outside Calcutta.

- The British government actively discouraged English education for Indians.

- Only a few missionary institutions offered English instruction during this period.

Against this backdrop of resistance, Macaulay’s Minute of 1835—advocating English as the medium of instruction—was implemented. Nehru notes that while the British hesitated to teach English, orthodox Brahmin scholars resisted teaching Sanskrit to Englishmen for their own reasons.

The William Jones Example

Nehru recounts how Sir William Jones, an eminent scholar and judge, desperately sought to learn Sanskrit. Yet:

- Brahmin scholars refused to teach him the language.

- Ultimately, a non-Brahmin Vaidya agreed—under strict and unusual conditions.

Through Jones’ translations, Europe experienced Sanskrit drama and literature for the first time. Nehru emphasises that India owes a “deep debt of gratitude” to Jones and other European Indologists for rediscovering India’s ancient literary wealth.

Why Nehru Believed English Empowered—Not Weakened—Indians

Nehru illustrates how English education did not alienate Indians but rather equipped them with the tools to challenge colonial rule:

- It allowed Indian youth to understand Western political thought, liberalism, and democratic principles.

- It introduced them to Burke, Shakespeare, Byron, and 19th-century English liberal politics.

- This exposure became instrumental in shaping modern political consciousness and ultimately fuelled the independence movement.

Modi’s portrayal of English as an agent of cultural destruction, therefore, ignores how crucial English was in empowering Indian nationalists.

Even Gandhi Benefited from English Learning

Mahatma Gandhi—steeped in the spiritual ethos of the Gita—never read it in Sanskrit, but through Edwin Arnold’s English translation, The Song Celestial.

He mastered English, yet retained a strong command of Gujarati, proving that learning one language does not erase another.

Modi’s argument about English eroding Indian self-esteem amounts to “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

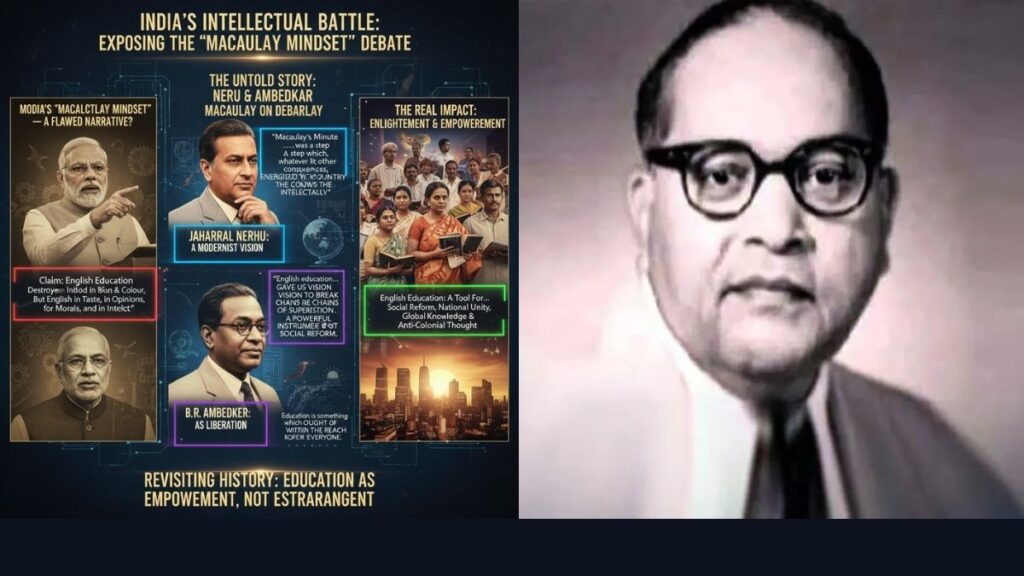

Ambedkar: Macaulay Was Key to Establishing a Uniform, Secular Criminal Code

B.R. Ambedkar provides yet another perspective—one that further complicates Modi’s claims.

In his 1946 book “Pakistan or Partition of India,” Ambedkar explains:

- Before the British, India was governed by Muslim Criminal Law.

- Macaulay’s Penal Code systematically replaced religious law with a uniform, secular criminal code.

This was a historic move—one that safeguarded equal treatment under criminal law for all Indians, irrespective of religion.

Ironically, those who champion a Uniform Civil Code today rarely acknowledge that Macaulay created India’s first fully uniform legal code nearly two centuries ago.

Ambedkar: Macaulay Recognised India’s Right to Self-Rule

Ambedkar also praised Macaulay’s early articulation of India’s right to self-government. In a 1955 resolution by the Scheduled Castes Federation, he quoted Macaulay’s 1833 observation:

- Indians were not barbarians.

- They possessed a distinct civilisation and culture.

- They therefore deserved the right to govern themselves.

Ambedkar contrasted this with the Portuguese refusal to grant freedom to Goa, arguing that even the British displayed a more progressive stance—at least in principle—through thinkers like Macaulay.

Conclusion: Modi’s Attack on the “Macaulay Mindset” Ignores Historical Reality

When viewed through the writings of Nehru and Ambedkar, it becomes evident that:

- English education did not uproot India but opened intellectual doors that helped Indians challenge colonialism.

- Macaulay’s role was not simply destructive—he helped democratise knowledge and establish India’s first secular, uniform legal framework.

- India’s nationalist awakening was profoundly shaped by English education, not stifled by it.

By rejecting English and vilifying the “Macaulay mindset” wholesale, Modi presents a distorted narrative that overlooks the immense intellectual, cultural, and political benefits English brought to India.

Far from weakening India, English served as a weapon of liberation—one that leaders like Gandhi, Nehru, and Ambedkar wielded to transform the nation.

Note: All information and images used in this content are sourced from Google. They are used here for informational and illustrative purposes only.

Frequently Asked Questions About the “Macaulay Mindset”

1. What does the term “Macaulay Mindset” really mean, and why is it debated today?

The “Macaulay Mindset” generally refers to the idea that English education in India was designed to create Indians who adopted British ways of thinking. The debate arises today because scholars like Nehru and Ambedkar highlight that English education empowered Indians, rather than weakening their cultural roots, contradicting claims that the Macaulay Mindset harmed India.

2. Did Jawaharlal Nehru agree with the criticism of the Macaulay Mindset?

No. Nehru believed that English education broadened Indian minds, introduced modern political thought, and helped Indians understand global liberal ideas. His writings show that the Macaulay Mindset argument oversimplifies how English learning actually strengthened, not damaged, India’s intellectual growth.

3. How do Nehru’s observations challenge the modern political use of the Macaulay Mindset?

Nehru pointed out that the British initially resisted teaching English in India, and scholars like William Jones learned Sanskrit only with great difficulty. This history contradicts the modern use of the Macaulay Mindset narrative, suggesting it ignores the nuanced, complex evolution of education under colonial rule.

4. What role did English education play in shaping India’s freedom struggle despite claims about the Macaulay Mindset?

English education introduced Indians to democratic ideas, liberal political philosophy, and global literature. Nehru, Gandhi, and many freedom fighters used these tools to challenge colonial authority—showing that the influence of English contradicted the negative assumptions tied to the Macaulay Mindset.

5. How did B.R. Ambedkar interpret the impact of Macaulay and the so-called Macaulay Mindset?

Ambedkar viewed Macaulay’s contributions positively in crucial areas such as law. He credited Macaulay with replacing religious criminal law with a uniform, secular Penal Code. His writings reveal that the Macaulay Mindset cannot be assessed only through cultural arguments because Macaulay’s reforms strengthened fairness and equality in India’s legal system.

6. Did Ambedkar believe Macaulay supported India’s right to self-governance, and how does this shape the Macaulay Mindset debate?

Yes. Ambedkar noted that Macaulay acknowledged India’s distinct civilisation and argued early for Indians’ right to self-rule. This perspective complicates negative assumptions about the Macaulay Mindset by showing that Macaulay was not entirely aligned with colonial suppression.

7. Why is the Macaulay Mindset often misunderstood in modern political discussions?

Modern political discussions frequently reduce the Macaulay Mindset to a simple narrative of cultural loss. However, Nehru and Ambedkar’s writings show that English education and Macaulay’s reforms played transformative roles in awakening political consciousness, rediscovering India’s heritage, and building a uniform legal system—contradicting one-sided criticism.

8. How did English education influence leaders like Gandhi, and what does this mean for the Macaulay Mindset argument?

Gandhi first experienced the Bhagavad Gita through an English translation and used English extensively while still mastering Gujarati. His example proves that English learning did not erase Indian identity. Instead, it enriched the freedom movement, showing that the Macaulay Mindset narrative often overlooks these positive outcomes.

9. What is the biggest misconception about the Macaulay Mindset according to historical evidence?

The biggest misconception is that English education uprooted Indian culture. In reality, English became a bridge to modern political ideas, global literature, and intellectual empowerment. Leaders like Nehru, Gandhi, and Ambedkar used English as a tool to challenge colonial rule, making the Macaulay Mindset criticism historically incomplete.

10. How can understanding Nehru and Ambedkar’s views help Indians reinterpret the Macaulay Mindset today?

Understanding their views offers a balanced perspective: Macaulay’s policies had flaws, but they also enabled intellectual awakening, legal uniformity, and global connectivity. Reinterpreting the Macaulay Mindset through their writings allows India to appreciate the role of English as both a cultural resource and a force for liberation.