Summary

The Untold Story: Education System of India

For decades, Indians have been taught that the British “gave” India its education system. But is this really true?

Nearly a century ago, during the 1931 Round Table Conference in London, a senior British official made an astonishing remark to Mahatma Gandhi:

“If the British had not come, India would have had no education system at all.”

Gandhi firmly rejected this.

With quiet conviction, he replied:

“If the British had not come, India’s education system would have been far better.”

This bold counter-claim sparked a debate that would continue for decades, eventually leading to one of the most remarkable investigations into India’s educational past—an investigation that changed how scholars view pre-colonial India.

Gandhi’s Challenge: “Find the Evidence”

After independence, one of Gandhi’s close associates, Professor Dharampal, asked him what his role in free India should be.

Gandhi reminded him of the London debate:

“I know India had a strong indigenous education system. But I lack documents.

Your task is to gather the evidence.”

Dharampal accepted this as his life’s mission.

For 40 years he travelled across Britain, France, Germany and other European archives—unearthing thousands of official documents written by the British themselves during the 17th–19th centuries.

The picture that emerged from these documents stunned him—India’s traditional education system had been far more extensive, inclusive and advanced than anyone imagined.

He compiled these findings in his classic work “The Beautiful Tree”, which has since become a landmark contribution to Indian educational history.

What British Surveys Revealed About India’s Education Before Colonization

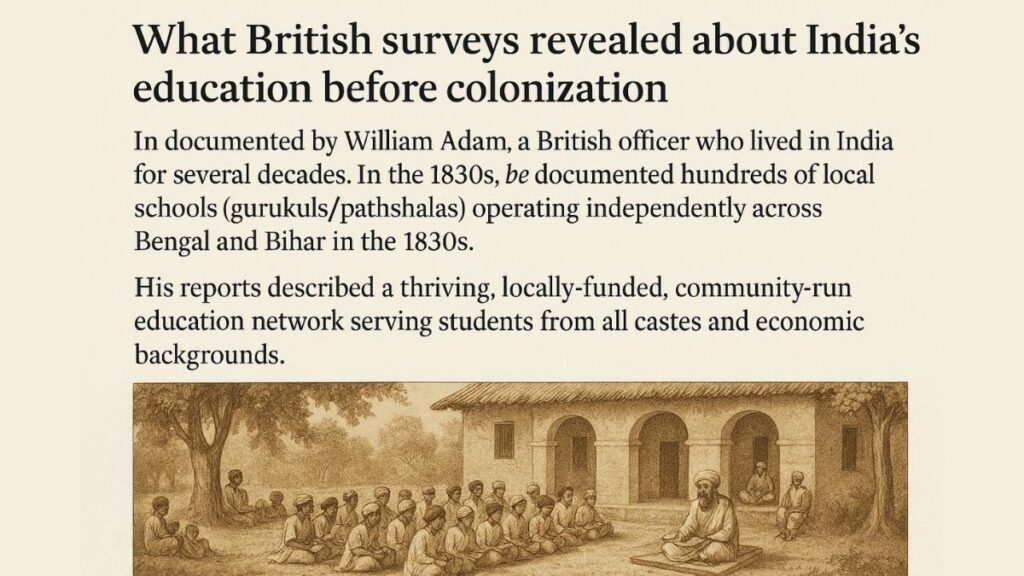

Among the most important early studies was conducted by William Adam, a British officer who lived in India for several decades.

He documented hundreds of local schools (gurukuls/pathshalas) operating independently across Bengal and Bihar in the 1830s.

His reports described a thriving, locally-funded, community-run education network serving students from all castes and economic backgrounds.

Other British administrators such as Thomas Munro, G.W. Leitner and local collectors in Madras and Bombay Presidency corroborated these findings.

These documents highlighted:

A widespread network of local schools

Every village cluster typically had at least one school, supported by community grants, land donations, or temple funds.

Subjects far beyond basic literacy

Mathematics, astronomy, medicine (Ayurveda & surgery), logic, philosophy, metallurgy, agriculture, arts, and various crafts were commonly taught.

Inclusive enrolment across castes

Historical surveys recorded high participation of non-elite communities—challenging the colonial narrative of education restricted only to upper castes.

Student-centred learning

The monitorial system, personalised teaching, oral exams, and intensive subject-immersion were commonly used.

Strong higher-learning centres

Ancient universities such as Takshashila, Nalanda, Vikramashila and provincial gurukuls continued influencing Indian scholarship well into the 18th century.

How Colonial Policies Disrupted India’s Indigenous Education

British reports themselves acknowledged that India’s education system was community-funded and self-sustaining.

This meant India remained intellectually strong—and therefore harder to control.

From the early 19th century onward, a series of policies progressively dismantled this system:

- Traditional teachers (gurus/acharyas) lost revenue due to new land settlements

- Educational grants to pathshalas were stopped

- Local languages were deprioritised

- English education became mandatory for government jobs

- Indigenous schools were discouraged and eventually collapsed

Within a century, the ecosystem that had thrived for centuries was replaced by a centralized, exam-driven, degree-oriented system designed to produce clerks, not thinkers.

The Psychological Impact: A Legacy That Still Affects Modern India

In 2005, during a speech at Oxford, then Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh expressed deep gratitude to the British for “giving India” its systems of education, law, science, and language.

British newspapers interpreted the speech as proof of India’s lingering mental colonization—a painful reminder that despite political independence, intellectual independence remained incomplete.

A Call to Action: Rebuilding India’s Educational Identity

Reformers today argue that it is time to rediscover India’s indigenous strengths:

- Holistic learning

- Character-building

- Ethical and spiritual grounding

- Deep subject mastery

- Self-reliance and practical skills

Modern gurukuls and alternative education centres across India are attempting to revive these principles—focusing on hands-on learning, sustainability, traditional crafts, critical thinking and cultural confidence.

The Real Question: What Direction Will India Choose Now?

India stands at a historic crossroads.

Do we continue with an education model designed in the 19th century for colonial administration?

Or do we shape a new model inspired by India’s own civilizational ethos, enriched by global knowledge?

The future of India depends on the path we choose today.

Share the Truth. Spark the Change. Shape the Future.

If India’s education story remains unknown, the next generation will inherit a broken narrative.

If it is told with honesty and pride, they will inherit the confidence to build a better nation.

The direction of a country begins with the stories it chooses to believe—and the knowledge it chooses to honour.

Note: All information and images used in this content are sourced from Google. They are used here for informational and illustrative purposes only.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About the Education System of India

1. What was the Education System of India like before British rule?

Before British rule, the Education System of India was primarily community-supported, locally managed, and deeply rooted in India’s cultural traditions. Thousands of village schools (pathshalas/gurukuls) taught subjects like mathematics, astronomy, logic, medicine, and crafts. British surveys in the early 19th century documented these vibrant local institutions operating across regions such as Bengal, Bihar, Madras, and Bombay Presidencies.

2. How did British policies affect the traditional Education System of India?

British land reforms and administrative changes cut off funding for local teachers and schools. Grants to traditional institutions were discontinued, local languages were sidelined, and English education became essential for government employment. Over time, the once self-sustaining Education System of India weakened as indigenous schools lost support and relevance under colonial policy.

3. What role did Gandhi play in defending the traditional Education System of India?

Gandhi strongly argued that the Education System of India was thriving long before the British arrived. During the 1931 Round Table Conference, he refuted the claim that India had no education structure before colonial rule. He later encouraged Dharampal to collect historical evidence proving the depth and strength of India’s indigenous education network.

4. How did Dharampal contribute to understanding the Education System of India?

Dharampal spent nearly 40 years researching archival documents in Europe, uncovering detailed British surveys of Indian education from the 17th to 19th centuries. His landmark work, “The Beautiful Tree,” revealed that the Education System of India was more widespread, inclusive, and sophisticated than previously acknowledged. His research remains a major reference in discussions about India’s educational heritage.

5. What subjects were taught in the traditional Education System of India?

The traditional Education System of India offered a broad curriculum including mathematics, astronomy, Ayurveda, surgery, agriculture, metallurgy, logic, philosophy, language, and various crafts. Learning focused on deep subject mastery, practical application, and character development rather than rote memorization or standardized exams.

6. Were all social groups included in the historical Education System of India?

British-era reports frequently noted that the Education System of India was more inclusive than colonial narratives suggested. Students from various castes and economic backgrounds were recorded in village schools, and many regions showed broad participation across society. In certain areas, surveys even documented significant enrolment of girls.

7. How did the colonial era change the purpose of the Education System of India?

The colonial-era Education System of India was restructured to create clerks and administrative assistants who served the British government. This shift moved education away from India’s earlier focus on holistic learning, practical skills, and community values, replacing it with a degree-oriented, exam-driven model centred on English-language instruction.

8. What is the psychological legacy of colonial influence on the Education System of India?

The psychological impact persists in the form of preference for English-medium education, undervaluing traditional knowledge systems, and a continued focus on examination-based learning. Many scholars believe the Education System of India still carries remnants of the colonial mindset, prioritizing external validation over indigenous wisdom.

9. Why is there renewed interest in the traditional Education System of India today?

There is growing recognition that the historical Education System of India emphasized critical thinking, hands-on skills, ethics, and holistic knowledge—qualities many feel are lacking in today’s model. This has inspired educators to explore modern gurukuls, skill-based curricula, experiential learning, and culturally rooted educational frameworks.

10. How can modern India blend global knowledge with the traditional Education System of India?

A balanced approach can revive the strengths of the traditional Education System of India—such as community participation, practical learning, and value-based education—while integrating modern science, technology, and global best practices. This hybrid model can help India build an education system that is culturally grounded yet globally competitive.

11. Did universities exist in the older Education System of India?

Yes. India has a long history of major learning centres such as Takshashila, Nalanda, Vikramashila, and many regional institutions that operated as universities. While many declined centuries before colonial rule, their legacy influenced the Education System of India well into the early modern period through Sanskrit colleges, madrasas, and gurukuls.

12. What key lessons can today’s policymakers learn from the historical Education System of India?

Policymakers can learn the value of decentralization, community-funded schools, vocational training, ethics-based learning, and culturally relevant curricula. The earlier Education System of India prioritized real-world competence, not just degrees—an approach highly relevant for India’s future.

13. How can parents contribute to strengthening the modern Education System of India?

Parents can promote reading, cultural literacy, practical skills, and local traditions at home. Supporting schools that value holistic learning and encouraging children to explore Indian knowledge systems can help restore aspects of the traditional Education System of India.

14. Why is telling the true story of the Education System of India important for the next generation?

Understanding the true history of the Education System of India instils confidence, cultural pride, and inspiration. When young Indians learn that their ancestors built thriving knowledge systems long before colonial rule, they gain a stronger sense of identity—and a clearer vision for the nation’s future.

15. What direction should the Education System of India take in the 21st century?

The Education System of India must evolve into a model that blends modern innovation with cultural depth. That means moving beyond rote learning, embracing critical thinking, strengthening vocational education, integrating Indian knowledge traditions, and building an education framework aligned with India’s civilizational ethos and global aspirations.